13 Location and Land Use

In this chapter we explore the spatial structure of American cities and the configuration of land use patterns. These topics (and, ‘why do cities exist?’) are usually the first two chapters of an urban economics textbook, so it would be good to complement this chapter with a fuller treatment of urban econ using something like Brueckner (2011) or Mills & Hamilton (1994), which are two of the classic texts. The geographic arrangement of employment and housing in an urban area is generally referred to as ‘spatial structure’ (Anas, 1983, 1985, 1990; Anas et al., 1998), and is often considered the foundation of urban economics (Alonso, 1964). It is a German concept in origin, later expanded and elaborated by Americans1. von Thünen (1826) is the progenitor of the monocentric model that describes intra-city variation in land-use types; Weber (1929) looked at transportation issues at the inter-city level to understand where different industries would locate, an early forerunner to optimization modeling. Christaller (1937) studied systems of cities, a precursor to fractal scaling and complexity science in urban studies (Batty, 2005, 2013), and Lösch (1940) combined their ideas with agglomeration and concentration effects.

“To retain a finite agenda, we think of urban land use as covering mainly the following issues: (a) the differences in land and property prices across locations, (b) the patterns of location choices by types and subgroups of users, (c) the patterns of land conversion across uses, and (d) the patterns of residential and business location changes within cities.”

– Duranton & Puga (2015)

The classic American concept of spatial structure is given by Burgess’s concentric zones, and expanded by Alonso, Muth and Mills into the bid-rent theory of the monocentric city. These build on the foundations of Von Thunen, Losch, and Christaller. Early development of these models was based on understanding why and where cities exist, and the recognition that transportation costs are a key element of urban function. By locating close to the city center, suppliers can make their goods available to more people and save on transportation costs, driving up land values at the core. The expensive land causes firms to invest more in construction costs, so they can squeeze more use from less land (land/capital substitution), which increases density and intensity of land development. The cost of transporting goods means that demand intensity falls with distance from the core, giving rise to density gradients. A tremendous body of work explores these patterns of “spatial structure” spread throughout the urban economics and economic geography literatures (Anas, 1990; Anas et al., 1998; Archer, 2005; Baldassare, 1978; Baldassare & Feller, 1975; Bennett & Haining, 1985; Clarke & Wilson, 1985; Daraganova et al., 2012; Garcia-López, 2012; Gottdiener, 1993; Greene, 1980; Helsley & Strange, 2007; Horton & Reynolds, 1971; Janson, 1971; Krehl, 2015; Orford, 2000; Peeters, 2012; Pfeiffer, 1980; Randon-Furling et al., 2020; Reia et al., 2022; Rogers et al., 2002; Rushton, 1969, 1971; Wu et al., 2021; Zhang & Sasaki, 1997, 2000)

13.1 Concentric Zones and Bid Rent

In the U.S., the earliest and best-known concept of spatial structure is the “Burgess Concentric Zone model” the describes how cities are organized by race and class. The Chicago school sociologists founded a core of neighborhood scholarship, examining the ways that people of similar race, ethnicity, and social status tended to sort into relatively homogenous zones of the city. Apart from being internally similar, the neighborhoods and land uses tended to follow a similar geographic pattern, where social status increased with distance from the city center.

The sociologists had little knowledge of the land economics literature at the time because it had not been translated from German yet. Burgess did not realize how similar his concentric rings were to Von Thunen’s

“Parallel to the development of the literature in land economics there has developed a literature in human ecology which also concerns itself with urban land values. In a seminal book in this discipline, Park and Burgess state:”Land values are the chief determining influence in the segregation of local areas and in the determination of the uses to which an area is put.” While the two disciplines have influenced each other, they have remained distinct, the land economists relating primarily to economics and city planning, and the ecologists to sociology.”

– (Alonso, 1964)

That is, while both groups of social scientists saw patterns of urban structure in flux, the sociologists used an ecological metaphor of invasion and succession of different social groups, and the economists explained the patterns via indifference curves in the land market. Their intuition is the same.

The simple and lasting insight from Von Thunen, Alonso, and the Chicago School is that different categories of land consumers (e.g. businesses vs households, Black householders vs white householders, stock traders vs coal manufacturers) have different purchasing power and demand for space near urban amenities (classically, the market center). Understanding the relative shape of these curves gives a remarkably good picture of how cities are distributed in space. Further, the shifting of these curves gives rise to urban dynamics. When technological changes shift demand for land (like falling transportation costs) the curve may flatten creating less central tendency and more sprawl. When residential preferences change (like when affluent whites’ preferences for accessibility outweigh their preferences for segregation) their demand for central land will increase, leading to gentrification.

This process also means that businesses benefit more from central locations than households.

In locations with high productivity relative to amenities, the return to commercial land use exceeds the return to residential land use. Therefore, these locations specialize as workplaces, with higher employment than residents and net imports of commuters. In contrast, in locations with high amenities relative to productivity, the converse is true. The return to residential land use exceeds the return to commercial land use, such that these locations specialize as residences, with lower employment than residents and net exports of commuters. If a location has both positive employment and positive residents, either the return to commercial land use equals the return to residential land use, or zoning regulations sustain a wedge between the returns to commercial and residential land uses.

– Redding (2023)

Thus, the steepness of the bid price curve may be viewed as an indication of how much the individual cares to be near the center in order to avoid commuting, and it is reasonable to expect that an individual with a steep curve will outbid an individual with a gentler one for central locations.

– (Alonso, 1964)

The classic example is a small tweak on Von Thunen’s model. Consider a city with three types of (land) consumers:

- retail (X)

- residential (Y)

- agriculture (Z)

Retail establishments get the most benefit from being centrally-located, so they have the steepest bid-rent slope and will be located nearest the city center. The isoline at \(a\) where retail rent is equal to residential rent defines the extent of the business district. Residential units get the next-highest benefit from access to the center, and have the second-steepest bid-rend slope (Land use Y), and the isoline at \(b\) defines the extent of the city. Anything further than \(b\) will be used as agricultural land. The isoline at \(c\) defines the edge of the metropolitan region (beyond this point, firms are nearer to another district, and will sell their goods at that location)

The important point is that the Bid Rent model uses simplifying assumptions like employment access as the sole utility factor, and the ‘featureless plain’ because they provide a nice illustration of the idea using only two dimensions. In reality, cities are polycentric and there are lots of benefits from urban land besides pure transportation savings to the workplace, but the model generalizes to accommodate those realities easily. Ahlfeldt (2011) shows that the bid rent model still performs very well, particularly once we allow some modern relaxations:

- Given the polycentricity of modern cities, distance to the CBD is less important than access to jobs–which is captured well by the gravity measure

- Network-based travel time is more important than pure distance

- other amenities, like environmental or school quality (or the initial distribution of population groups) also matter

Intuitively, this is all straightforward. People do not like to travel (Zipf, 1949), so they gain utility by living near amenities they enjoy (because it costs less to enjoy those goods). The amenities might be jobs, recreation, social groups, or nice climates. When group-level preferences for different amenity bundles change (or technology changes that facilitate a different level of enjoyment, e.g., telecommuting), then we get changes in the urban fabric.

Urban growth shifts the bid rent function up and to the right (without changing its slope), like adding a new ring to a tree trunk, which means the building stock inside a particular ring of development tends to be of a similar kind (e.g. office buildings vs residences) given the bid rent functions presented above, and also that buildings tend to be the same age. As growth happens, the first ring of residential units will be redeveloped as office buildings, and the first ring of agriculture will be converted to residential, etc. The interaction between these redevelopment cycles and the demographic characteristics of the land consumers (e.g. the largest age bracket of land purchasers) leads to housing market filtering (Galster, 1996; Grigsby, 1964; Grigsby & Corl, 1983; Lowry, 1964; Lowry, 1960; Megbolugbe et al., 1996; Rapkin & Grigsby, 1960).

We will return to these concepts in the last chapter.

13.1.1 Spatial Structure in Context

The historical context of the bid-rent model and its lineage are critical for understanding its applicability today. Von Thunen was writing about agrarian world in pre-industrial society. In his case, all the goods are all agricultural, produced on the outskirts, and then sold at a central market. The cost of transporting goods from the source of production to the marketplace is basically the sole component of location utility; it’s all that matters. Of note, it is also land, explicitly, that has value at the time… The wealthy landowner class rents its land to the agricultural working class for lodging, farming, hunting, fishing, etc– but it’s land that allows all of that to happen3. Also, rural Germany is not wildly cosmopolitan at the time, so his concern is only about different classes of land capital (income stratification) not ethnicity or education, or age, etc.

The Chicago School ecologists wrote during the industrial revolution, the great migration, and the advent of city planning (Moore, 1921). These are two of the largest shifts in the U.S.A.’s economic geography and demographic geography (happening simultaneously) and there is a lot happening in Chicago at the time. Consider American racial conflict in the era. We are roughly a generation after Reconstruction, and there is a massive differential in wealth, income, and social status between Black and white Americans. Immigration is booming. Transportation is still very expensive, so all of these people are moving into cities, where the economic power is also relocating (i.e. where the jobs are). With many different groups colliding in cities for the first time, “competing” to live and work in the same space, it is easy to understand the ecological metaphor.

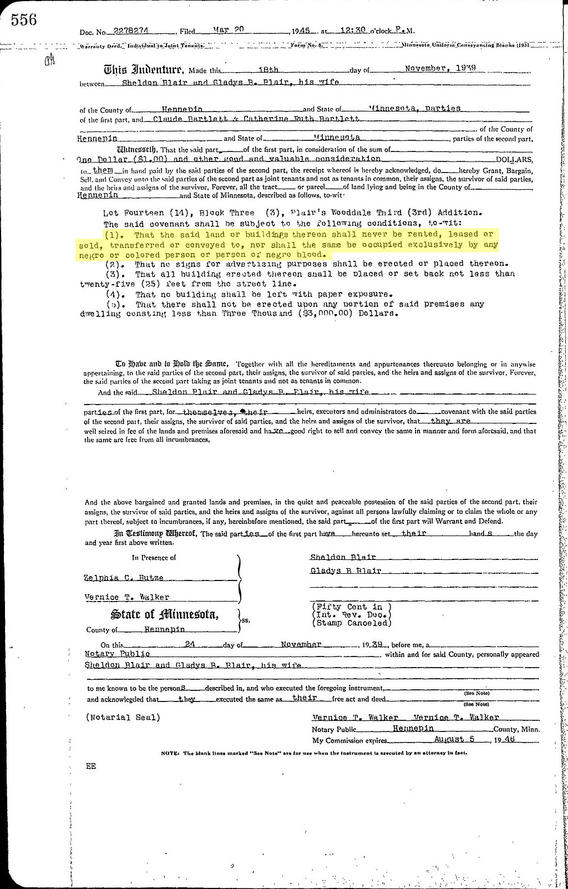

Social network homophily is an obvious driver of location choice and neighborhood formation at the time because a combination of cultural factors (e.g. language barriers), social capital, explicit racism, and differences in the initial distribution of purchasing power between groups. The ecologists noticed the strong influence of social differentiation on spatial differentiation4, but they paid less direct attention to the fact that the resulting multivariate segregation was not just “natural area” formation, but also the result of brutally-enforced public policies like racial covenants or differential lending priorities (e.g. redlining). That is, in addition to the bid rent function, proximity to social groups became an important factor in location utility (but not overwhelming, because there were still viable policy measures to exclude certain groups from desirable locations).

The Regional Science hall of fame (Alonso (1964), Muth (1969), Mills (1967)) wrote during the era of white flight and suburbanization, another period with multiple concurrent shocks. Widespread automobile ownership and construction of the interstate highway system caused transportation costs to fall and bid rent curves to flatten dramatically, so the suburbs grew because commuting back to the city was (and is) cheap (an important first glance at the importance of travel time impedance as an abstract measure of space/distance rather than Euclidean distance that proxies it) (Levinson, 1998). This is also the era of Civil Rights and Fair Housing legislation, which removed the legal ability for the white population to exclude others from neighborhoods, schools, and grocery stores. So they simply moved out and took their resources (read: taxes) with them (Jargowsky, 1996; Logan et al., 2023; Muth, 1985; Wilson, 1987, 1996).

Thus enter into the equation of spatial structure two critical variables: the elasticity of mobility (Sampson & Sharkey, 2008; Sharkey, 2008, 2013) and local land-use control. Moving costs do not scale linearly with income; the more income you have, the less it costs to move to a new location, which provides a better opportunity to optimize (DeLuca et al., 2024; Muth, 1985). In a perfectly Tieboutian (market competitive) world where information is perfect across subgroups and mobility is costless, then municipal differentiation is a good thing because it allows everyone to sort into their preferred neighborhood bundle. But when some groups are more mobile than others, it allows them to be free riders in the sense that suburban commuters can consume jobs in the city, but spend their tax dollars in a suburban municipality.

This is exactly what happened through the period of deindustrialization [Wilson (1996); Wilson (1987);]. Commute-times remained constant even though commute distances grew (Levinson & Kumar, 1994), Large-lot zoning kept property values in the suburbs high, and the racial wealth differential combined with predatory lending, real estate steering, etc, provided the rest of the white-flight sorting mechanism (Bradford & Kelejian, 1973). This reconciles the bid rent model with the concentric zone model; even though the most expensive commercial land is near the urban core, American cities are structured with wealthy white communities in the suburbs and minority communities in central cities because of cars and racism. And people making location decisions today still make choices based on where these groups live.

13.1.2 Bid-Rent Functions in the Post-Pandemic Era

The bid-rent model still matters for understanding cities today, and remains among the most intuitive models for understanding spatial market behavior.

The COVID-19 pandemic was a huge shock to urban systems, and in many ways it was a big natural experiment for understanding agglomeration forces and demand for urban land. “Essential workers” reported to their workplaces at stores, gas stations, dentists offices, and more, while other occupations (often entire industries) moved to remote work. For many workplaces, the pandemic showed that remote employment is a good substitute for in-person employment, so many jobs have remained remote or changed to hybrid-style, even after the return to daily life.

Remote work has obvious implications for cities, because why would companies waste a big share of their budget on urban real estate when people work from home? If businesses no longer care to locate in cities, then might cities fall into decline, similar to the way deindustrialization decimated the rustbelt? Some were even claiming we would develop into “donut cities”, with urban real estate values plummeting in cities. But this is a clear misunderstanding of land economics and intuition from the bid-rent model makes clear this is not going to happen.

Homelessness in cities is a sign of excess demand for urban land, not excess supply… If there is an enduring housing crisis because residential land values in urban areas are persistently too high, then cities are not hollowing out. They are just densifying with people rather than densifying with units. This leads to the opposite conclusion from Davidson: we should build more housing in cities–the demand is obviously there (i.e. the deindustrialization metaphor is wrong). People are leaving San Jose because they can’t afford it, not because they want to be somewhere else. Thus, you can increase revenue by adding units rather than raising property taxes. In other words, there is a gap between the land supply and the residential bid rent curve, and all we need to do is reallocate supply.

In more formal terms, what is happening is a flattening bid-rent curve for some occupations and some industries, which will certainly lead to some companies exiting cities. But bid rent functions are stratified by different types of land consumers, and while one demand curve is flattening, others are not (they are probably even steepening). Many industries like retail, entertainment, education–even finance–still do most of their business in-person (and therefore in cities), so their demand is not going anywhere. Further, consider what this change does to the residential demand curve. If you no longer need to commute to your job, then you probably prefer to be near other amenities you enjoy like recreation–or retail and entertainment. This means that places like Park City, Bozeman, and Honolulu become more attractive for the former and Chicago, New York and L.A. become more attractive for the latter. Less congestion from commuter traffic might even make these places more enjoyable! In other words, demand for “accessible” (i.e. downtown) space is not falling, it is just shifting hands (McMillen, 2003).

And as a result, today many cities are rezoning downtown space from commercial to residential to help match supply with demand (Brueckner et al., 2023) 6. Not only are cities not going away, but this small increase in supply could help make a dent in the urban housing crisis. We can avoid donut cities as long as we use land-use regulation effectively because holes are artificial. The land market would not allow a hole since, as we have just seen, residential demand for downtown space is not decreasing. Thus, the only way to induce a hole is by setting aside land supply for commercial use (where demand is falling)

13.2 Land-Use Regulation

Understanding the interplay of these forces, and manipulating the supply side of the land market is central to public policy and urban land-use planning (Knaap et al., 2001; Knaap et al., 1998; Knaap & Nelson, 1992). Although rarely acknowledged for this particular insight, Alonso (1964) was acutely aware that land use regulations could effectively harness these differential bid rent curves to achieve better social integration. While urban renewal was the issue of his era, his understanding of density bonuses and the use of public policy to manipulate land supply is among the earliest articulations of inclusionary zoning to maximize public welfare. The same logic could be used today to help mitigate the displacement harm of gentrification. (Of course, he also understood it required a metrpolitan-scale zoning jurisdiction to implement these kinds of land-use regulations effectively)

This strongly suggests that a vigorous metropolitan zoning regulation is a necessary adjunct to current renewal practices. This zoning would set minimum-lot requirements in central locations, changing the occupancy to higher incomes, and maximum-lot regulations in peripheral locations, changing the occupancy to lower incomes. It must be observed that current zoning practice tends to defeat current renewal practice by setting high minimum lot restrictions in peripheral locations. It must also be observed that, since metropolitan government is an obvious necessity for the comprehensive, coordinated zoning just suggested, the recognition of the interdependence of zoning and renewal activities constitutes a very strong argument for metropolitan government, at least with respect to these functions.

In other words, even at the inception of urban economics, Alonso articulated a lasting insight about the relationship between spatial analysis and the demand for land. And that relationship is so strong–and so well-understood–that we can use land policy to define supply constraints which will effectively shift capital in space to maximize public welfare. To raise land values in the city, you enforce minimum lot sizes downtown, which leads to densification, and you enforce maximum lot sizes in the suburbs, which decreases sprawl and increases housing supply (it also decreases the attractiveness of suburban real estate relative to more accessible places, which raises demand downtown). Both of these are antithetical to current zoning practice.

Just as important, Alonso argued that a metropolitan scale zoning authority would be necessary to actually enforce these regulations because housing markets and labor markets are regional in scale. Absent land-use regulations at a matched regional scale, there is a clear incentive for municipalities to develop into “Tieboutian clubs” (Brueckner & Lee, 1989; Heikkila, 1996; Verspagen, 1999) that are designed to hoard privilege (Candipan & Sampson, 2021; Galster, 2023; Troost et al., 2023).

Land-use policy defines some set of regulations over a pre-defined spatial scope. We can think of it as a polygon overlay in a map. The classic example is zoning, but other well-known examples include redlining, urban growth boundaries, tax increment financing (TIF) districts, or enterprise zones. These are all discrete boundaries that define a uniform treatment (in theory) to all people/households/businesses located inside the polygon. By definition, these policy boundaries create exogenous shocks to the spatial system–and critically, those shocks spill over into other parts of the system, which are characterized by different linkages. One classic example is understanding tax policies in neighboring regions.

Take a municipality embedded within a larger region. The municipality is related to other municipalities nearby, because they belong to the same region (and thus the same housing and labor markets). But they represent different portions of the housing submarket, and each municipality has zoning and taxation authority. If one municipality enacts exclusionary zoning that prohibits the development of affordable housing, it changes the population structure of the nearby municipalities because some households can no longer afford to live in their original location. This changes the interaction structure within each municipality. For example, if the municipality is internally-segregated, then all the low-income students may end up in small subset of neighborhoods and schools (which themselves interact at a local level) (Brueckner, 1995; Henry et al., 1997).

13.3 Agglomeration & Specialization

Bid rent provides a model for understanding how cities are internally organized, and laid out relative to the market center (the central business district). But this begs the question, where is the market center? And why is it there? The ‘economics of location’ explains why businesses cluster together in space. This tradition belongs to Marshall (1920), Weber (1929), Hotelling (1929), Lösch (1940), Christaller (1937), Ullman (1941), Hoover & Vernon (1959) and Isard (1949).

Access to consumers isn’t the only benefit of locating downtown. By centralizing goods at a marketplace located at the core of a city, suppliers also benefit from positive externalities. There are spillover benefits that make it more productive for firms to co-locate. When cities specialize in a particular industry or good, they can trade the surplus to other cities to make both places more productive, which gives rise to regional economies and locational specializations (Eberts & McMillen, 1999; Goldner, 1971; Lowry, 1964; Lowry, 1960; Whitehead, 1999).

France has grapes, Appalachia has coal, NYC has the stock exchange, and Silicon Valley has… Stanford. The different qualities of those goods (i.e. wine versus software) imply different things about the importance of transportation costs and relative utility of spatial proximity for generating positive spillovers (Henderson, 2003).

“Cities emerge because of productivity gains that accompany the clustering of production and workers. Also known as agglomeration effects, these gains arise from superior matching of workers and jobs, knowledge spillovers that accelerate the adoption of new technologies, expanded opportunities for specialization, scale economies in the provision of common intermediate inputs, and lower transportation costs. Because agglomeration effects give rise to cities, most economic activity, and therefore growth, occurs in cities.”

– Davis et al. (2014)

Whereas for former description of spatial structure describes the causes underlying residential versus commercial land use, this process describes why different sectors emerge in different parts of the city (or regions of the country)

However, following Marshall (1920), three main sets of forces for agglomeration are traditionally distinguished, which reflect the costs of moving goods, people, and ideas. First, firms may locate near suppliers or customers in order to save on transportation costs. Second, workers and firms may cluster together to pool specialized skills. Third, physical proximity may facilitate knowledge spillovers, as (in Marshall’s words) “the mysteries of the trade become no mystery, but are, as it were, in the air.” Another line of research dating back to Smith (1776) emphasizes a greater division of labor in larger markets, as examined empirically in Duranton and Jayet (2011). More recently, Duranton and Puga (2004) distinguish between sharing, matching, and learning as alternative mechanisms for the agglomeration of economic activity. Although these mechanisms are well understood conceptually, there is relatively little evidence on their empirical importance, with a few exceptions such as Ellison, Glaeser, and Kerr (2010).

– Redding (2023)

Alonso was actually Argentinian but fluent in German and English↩︎

There are many incarnations of this figure that blends Von Thunen and Alonso, but this particular version is lovingly recreated from Steve Deller’s lovely slide deck on community economic development↩︎

Tangentially, we tend to forget that “gentrification” refers to the end of this era in the UK, when land was transitioning away from being the predominant means of production, and that cities in the UK became cool during the post-war period when the “landed gentry” (the landowner class) decided to move there (Glass & Rodgers, 1964). In the U.S., our pre-industrial economic system was slavery and Reconstruction was concurrent with the industrial revolution. The Jim Crow era was our transitional period, which means our ‘gentry’ are plantation owners (and our Robber Baron class all made their money from cities, explicitly, and never really left). So the British metaphor doesn’t always translate. Gentrification here is really about our petite Bourgeoisie class.↩︎

Despite its imperfections, the methods from human ecology remain very useful tools for understanding cities and are elaborated in the proceeding chapters on Chapter 19 and Chapter 22↩︎

Jack Delano, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons↩︎

See: https://www.nytimes.com/2023/09/28/realestate/theres-a-building-boom-but-its-not-for-everyone.html↩︎